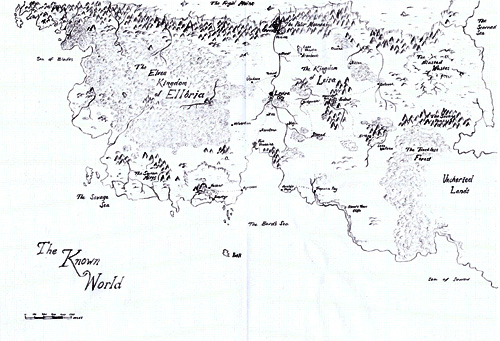

World Information

- By Damo

Geography

Gönd is a largely undiscovered world, at least as far as the People of Leyira are concerned.

The known world stretches only as far west as the elven kingdom, which is vast. To the north, the icy plains beyond the palir mountains prevent deep exploration beyond the camps of the goblin khans.

The east of Leyira sees much exploration an expansion, though he who wanders too far sees a broken and savage land, both difficult and dangerous to traverse. Travel far enough and one is met by sea.

To the south lies a vast ocean. Many ships have set sail in search of new lands, but of those who return, only a few report sightings of land. Only one ship returned having sighted intelligent life, Captain Rhys, who was met by a tribe of black skinned savages far to the south and east. Rhys is planning another expedition soon, with the intention of setting up trade. Their lands are apparently rich with Mithril. Many dwarves are lining up to set sail… their desire for the strong silver overpowering their aversion to oceanic travel.

For most however, the Known World provides more than enough challenge. Harsh winters, fractious in-fighting, marauding goblin tribes and worse to the East are ever present perils for the denizens if Leyira.

Vartich

The Dragon Aeries of Vartich is a Legendary city populated solely by Dragons. No-one in Leyira has even seen a Dragon for hundreds of years – let alone travelled to their homeland. However, the legend of the Dragons and their homeland persists to this day. It is said that, some day, the Dragons will return to the Known World and rain down fire and destruction upon its peoples… reclaiming their place in Gönd as the dominant race.

Denizens

After centuries of sporadic warfare and border disputes following the founding of the Kingdom of Leyira, Humans, Dwarves and Elves now all live in peace. The cities of Leyira provide the melting pot in which they all come together.

Human began life as nomads, but soon developed a proclivity for changing their environment rather than adapting to it. This tendency, more than anything else has made them the best farmers and city builders that Gönd has to offer. In a very short time, their kingdom has expanded to become the largest and most populous in the Known World.

Early on in their encounters with Humans, the Elves and Dwarves both offered to help them build their cities. From the Dwarves, they received knowledge about masonry. From the Elves, they received a controlled supply of sturdy wood – thanks to the Elven Druids. In return, the humans traded farming produce – invaluable in times when nature yielded little. Finally, the Elves taught the humans how to control and respect magic. It was for this boon that the humans gave their kingdom the Elven name of Leyira.

Dwarves have their main power base under the Palir Mountains. How far it actually extends under Gönd is unknown to surface dwellers. The Hundred Years War between dwarves and humans followed the founding of mines in Otraxis: while they were unconcerned with gold panning and so on on the surface, they considered establishing mines to be an invasion, and responded in kind. After slightly over a century of sporadic guerilla warfare and terrorism, peace was established, and as part of the settlement, Otraxis has to submit permits for new mines to the Dwarven Kingdom for review, and are limited in the amounts of ore that can be extracted.

Dwarves are frequently found in human cities – as they trade to survive. Dwarves gave up farming and hunting long ago. The Dwarves are perfectly willing to trade their own gold and jewels through Otraxis for the things they can’t get underground, like wool and fruit and so on.

The dwarves are arranged in clans, all of whom have sworn fealty to their King. To be a clan, a dwarven family must own a mine: to lose access to a family mine is a great shame for them. They have an oral history more extensive than any of the other races except dragons, and greatly value history. They venerate the elderly for their experience and wisdom, and make sacrifices to their ancestors. After death, dwarves are embalmed and placed in family crypts where clan elders can consult their spirits (again, dying without being returned to their crypt is a great shame). Dwarven Witches tie the power of their ancestors into artifacts of power, and steer the fortunes of their clans.

Dwarves are often Fighters, Rogues and Witches, but rarely Wizards. Dwarven Sorcerers often have Draconic blood.

Elves still live as hunter gatherers and barbarians, being powerful enough naturally in magic to have no strong need to establish permanent homes. Still, they founded the first Great Kingdom of Gönd (excepting, perhaps, the fabled Dragon Aeries of Vartich), naming it Ellôria, and maintain something of a moving city within its boundaries, the Kindom’s capital of Nyl’Doren.

The Elves are ruled by two courts which travel the realm with the winds in palatial tents of silk and shadow, maintained by magic. They guard their borders extremely closely. They are flighty, unable to concentrate for long periods of time, and as quick to take offense as to forget about it. They are fascinated by lesser-lived races and their amazing powers of concentration and memory, and sometimes steal children or musicians to entertain them as curiosities. They also raid nearby towns and caravans (and each other) to steal “valuables” or whatever catches their eye.

For the most part, though, the Elves stay in their homelands and heavily forested areas. Few have the stomach for the claustophobic human cities. While other races are welcome on Elven soil, the protocols that must be followed are prohibitive and harshly enforced. As a result, few but the Sylvan folk tarry long in lands claimed by the Elves.

It is said by some scholars that when gods created the world, they instilled each race with different measures of Magic and Reason. Dwarves have little magic, but are ordered, dour, skilled and have long memories. Humans have equal amounts of both. Elves are weak in reason, rationality and perhaps even sanity, but very strong in magic. Many Elves are Sorcerers, Wizards, Rangers, Rogues or Barbarians.

Goblins, although not a powerful race generally, are important to the people of Otraxis because they make war in the steppe land north of the city, across the Palir Mountains. They destroyed the Dwarven Kingdom’s above-ground cities, destroying many ancestor crypts, earning the eternal enmity of the dwarves, but humans trade with them occasionally. They are a fierce, warlike race, forever fighting each other, the mountain orcs (whom they despise), and whomever else they can find. They are partially nomadic, as home in the saddle as on foot, roving the north in summer but returning to the city of Shamshi-Abad, where violence is forbidden (or at least, heavily discouraged), in winter. They are ruled by the Goblin Khan, Grishnya-Khan. They consider long moustaches a sign of virility. Many goblins are Cavaliers or Fighters.

Other humanoids

Living amongst the cities of man, you will find Halflings, Half Orcs and Half Elves… each with their own niche in life. Halflings are the hosts and the entertainers. Their taverns have the best atmosphere and food anywhere. Half Orcs are the body guards and consumate mercenaries. It is rare to find a caravan in the wild without at least a few Half Orc guards. Half Elves are the diplomats, their unique situation providing an excellent perspective on most situations. Gnomes are rarely to be found in Gönd, preferring to live underground, tunnelling deeper than even the Dwarves dare to go. They are cunning and resourceful and are found most commonly, when on the surface, in Dwarven settlements.

Worship

The Gods of Gönd are represented by a circle or coloured wheel, representing the elemental forces that compose the world.

Although the Elder Gods created Gönd and seeded it with life, their thoughts are too alien, their power too great and their burial too long for most of the younger races to remember their existence, let alone worship them. They have been forgotten by the humans and almost all of the Elves, and, although the Dwarves remember them in their ancient songs, they think that to speak of the Elder Gods is taboo. After all, they’ve been trapped by their children for millenia – they’re not going to be happy when they get out, and taking their names in vain may only draw their attention.

The Elder Gods are remembered only as brute elements the younger Gods used to create Gönd, not intelligent beings, and occassionally drawn upon in oaths and curses: “By Flame!”, “Water, drown you!” and so on.

However, the Elder God’s creations, the dragons, remember their masters, whose imprisonment has caused the dragon’s long decline. Some say the dragons work with reptilian patience to free the Elder Gods. In any case, they have certainly told some carefully chosen members of the younger races the truth and power of their Elders, who have gone on to draw a fraction of their power as druids. They show their allegience to their secret cult by blasphemously crossing the circle of the Gods, to symbolise the imprisonment of the Elder Gods. Only the highest of the druidic orders (the hierophants) know the truth, however. Most druids genuinely believe they are simply worshiping nature – while every spell they cast brings the Elder Gods closer to freedom.

The younger races of Gönd worship the younger Gods. Unlike the Elder Gods, the Gods have names and personalities, and are more amenable to mortal understanding. They are not worshipped individually by most people; the elements must function together as a whole for Gönd to continue, and so must the gods.

Instead, humans worship them jointly in circular temples. The gods collectively are worshipped at a multifaceted altar at the centre of the temple, and, in the largest temples, each god has its own shrine on the outside of the circle, opposite its face on the main altar, where people can pray for specific interventions. Each has its own feast day once a year (often tied to the seasons).

Going clockwise round the circle:

1. Molkai (Mist; Air-Water): The god of trickery, the hidden, the unknown, the insane, lost things, choices, freedom, rebellion and the future. Molkai protects children and the mad and is the only God capable of parting the Mists of Time to see what the future holds. Molkai’s touch can bring madness or heal it. The enterance to Temples is traditionally through Molkai’s shrine.

2. Branchala (Smoke; Air-Fire): The god of passion, destruction, storms, spring (when there are storms), creativity, artists, sensuality, beauty, music, lovers. Branchala is god of all that is powerful but changeable, or related to the passions.

3. Eurus (Light; Air-Fire): The god of the truth, purity, the sun, protection, the law, justice. Eurus is god of protection generally (whereas Morkai protects the weak, Enlil supports the strong, and Tala supports mothers) – Eurus’ name is frequently invoked by armourers and those who make walls, or those who need refuge from persecution. Eurus oversees judges and watchmen.

4. Enlil (Magma; Earth-Fire): The god of summer, heat, warriors, strength, victory, the hunt. Enlil oversees all of the martial arts or anything that involves pitting something’s strength against the other. Enlil is god of cunning, if only in the area of contest, and not in terms of general intelligence.

5. Lathenna (Metal; Earth-Fire): The god of craftsmanship, discipline, technical ability, science, learning, transmutation (as in, the ordered change of one thing to another), order, commerce (as in, the impartial actual running of the system as a whole). Lathenna is a sober god of the intellectual and skilled arts.

6. Tala (Plants; Earth-Water): The god of plants, the harvest, autumn, birth, the home, wild things. Tala oversees mothers or those who must care for children, but also represents the dangers of the wild: poisons, animals and so on.

7. Chemosh (Ooze; Earth-Water): The god of avalanches, disease, decay, healing (withdraw thy favour!), chaos/disorder, the moon, luck, drunkenness, random chance. Chemosh is a wild god whose name is invoked more often to ward off than to invite in. Chemosh ensures brewers and distillers are successful, and looks after the drunk, thieves, gamblers and so on. Chemosh symbolises the collapse of solidity into fluidity: whereas Molkai symbolises rebellion in the sense of overturning a social order for the sake of establishing a new order, Chemosh symbolises the destruction of order entirely. Chemosh’s feast day is a drunken revel when status is meaningless.

8. Emesh (Cold; Air-Water): The god of cold, winter, death, snow, the stars (crystals of ice in the sky), navigation, wealth (because the dead are buried with grave goods), sleep. Emesh is the last god as Molkai is the first. Emesh symbolises endings, but also the transcendence of endings: the stars, the eternal and the unknowable. Emesh protects graves, and brings an end to pain. Emesh is also the patron of adventurers (who are also known as the Children of Emesh).

You will notice there are no gods of good or evil or racial gods. This is intentional.

So, a fighter about to go off to war might make offerings to Lathenna, for strength of arms, Eurus for protection, Emesh in case he dies, and a big one to Enlil for strength and victory. A woman about to give birth might make offerings to Emesh to stay his hand, Molkai to protect her child, and a major one to Tala for the birth itself. A judge would pray to Eurus for wisdom. Sailors pray to Emesh for navigation, Lathenna for their boat and skill, Chemosh for luck in fishing, and Branchala to avoid storms. Someone lost in a snow storm would probably pray to Emesh and Molkai.

In contrast, clerics are those who become so indebted to a particular god that they serve their purposes exclusively (although not to the point of neglecting the other gods). For example, a man may serve to swear Emesh exclusively in return for the lives of his family during particularly harsh winters. It is a formed of indenture or thankfulness than pure piety, since piety has no place when there is no reason to doubt the existence of the gods and evidence of their power is everywhere (e.g. in clerics).

Magic

Magic is a direct consequence of the Elder Gods. Their raw energy feeds Gönd’s sorcerers and wizards. Unlike priests, who pray to specific gods for their power, wizards use arcane rituals and gestures to tap into the power of the Elder Gods (unbeknownst to the caster). Sorcerers are particularly sensitive to the emanations of magic, and their small empathy with the Elder Gods allows them a natural talent for magic. Many sorcerers, without knowing why, turn slightly to the north before casting a spell.

Only the Dragons and a select few Elves know of the true origins of magic – but none communicate directly with the Elder Gods. The Dragons may worship them, but they must use arcane gesture like any other wizard to tap into their power.

How about…

There is the division between the Elder Gods, who created the world and populated it and are now buried in the Lands of Everwinter in the far north, and the other Gods, who are their children and aren’t buried.

I like the Dark Sun idea of elemental clerics, who have been supplanted by paraelemental clerics. Otherwise you just end up with an endless fascimile of the same dull pantheons (“Goddess of Healing and Childbirth, God of Death, God of Dwarves, God of Elves…”)

So, the Elder Gods are the powers of raw creation: Fire, Water, Air and Earth. They are unfettered and frightening, beyond mortal comprehension, because they create and destroy and change so continuously.

Their creation, the original inhabitants of the world, are the Dragons, who embody the four elements and are almost as powerful and aloof as the Elder Gods, which only they give more than lip service to anymore. So you have Red Dragons (Fire), Green or Blue Dragons (Air), Black Dragons (Water) and um… Earth Dragons. Perhaps Brown or Grey Dragons with the stats of Blue Dragons, that breathe rivers of crushing earth instead of lightning?

The Elder Gods’ children are the paraelemental new Gods, who actually have names and are worshipped by the younger races. So you have:

Earth-Fire: Metal and Magma

Earth-Water: Plants and Ooze

Air-Fire: Light and Smoke

Air-Water: Mist and Cold

I suggest Mist or Smoke as the element for the evil god (Molkai), since they’re both about concealment, and he’s a trickster god. Shadow is too passe.

And the mortal races were created from the blood of the Gods. Dwarves could be formed from Earth or Metal (depending on whether you want all the major races to be Elemntal or Paraelemental), elves from Fire (because they’re flighty and mercurial) or Air (for the same reasons) or Water (again – see how versatile my cosmology is?) or Plant. Humans could be Fire or Metal. If you want Dragons created here instead of by the Elder Gods, I’d make them Air.

So that’s dwarves (Earth), elves (Water), humans (Fire) and dragons (Air);

Or dragons (Elder Gods, all elements), dwarves (Metal), elves (Plants), humans (Mist?), etc.

I personally incline, having thought about it, to having the Four Races equate to the four elements, and all the lesser ones be either paraelemental or Molkai’s perversions of the elemental races (goblins are perverted dwarves, orcs are perverted elves…). It explains why the Four Races are special.

So that’s a grand total of 4 Elder Gods (or at least, 4 types of Elder Gods, since their actual identities are beyond comprehension) and 8 paraelemental younger race Gods.

Thoughts?

I like a lot of the ideas you’ve got there… especially dragons as the creations of the Elder Gods. That could explain why the next generation of Gods were jealous.

Elder Gods representing the elements is also a great idea, especially in light of the new rules.

The Paraelemental Gods are also great… not sure about “Ooze”… but the general idea is great. I’ll just remove the reference to the Elder Gods’ grand children. Mokai would indeed be appropriate as mist.

As for the other 3 of the 4 great races, I’m not such a fan of them representing elements. I think having a combination of all of the primal elements required to create each of them works best. As for why they are special, I think that they are the first civilised races and rule the great Kingdoms of Gönd should be enough. The dragons, created first and on purpose, are in decline – but the other races are flourishing.

That okay with you? If so, I’ll incorporate it into the timeline and the campaign information.

What’s wrong with Ooze? You try combining Earth and Water in a meaningful way that doesn’t come up with mud. Anyway, don’t tell me you’re not itching to dump gelatinous cubes, black puddings, mud men, and ooze mephits on us. No one said it had to be a major god.

Although, come to think of it, anyone living beside rivers and hills or on clay is going to want to propitiate it to avoid being crushed in landslides or washed away in floods and so on.

I’m not too attached to the idea of the younger races representing elements, but elves = plants and dwarves = stone in every other system *ever* so I thought I’d codify it. I imagined it’s more of a symbolic thing anyway, to explain their racial proclivities – you know, “We may be mammals just like elves and dwarves, but we have spirits of fire. Freedom is in our souls, not weak water or confining earth.”

I imagine they’d all have all 4 elements in them anyway: body (earth), blood (water), breath (air) and spirit (fire). It’s who’s got more of what that’s important.

But if you don’t like it, leave it out.

Oh, and Ooze might also cover oozy things like decay and disease and healing. You pray to Chemosh, god of Ooze to withdraw his favours and stop things getting manky.

Okay, I agree… ooze is appropriate. I like where you’re heading with this.

Would like to come up with the names and spheres of influence for the pantheon of Gods?

It should be noted that humans (and most Elves) don’t even know about the Elder Gods, much less their names.

Given all the races seem to be able to inter-breed (sorcerers, half-elves etc), does anyone like the idea that gnomes are dwarf-elf crossbreeds and halflings are human-dwarf crossbreeds?

This is a separate issue to whether you like those races or not.

Although, if they’re just crossbreeds, they’d have less of a place in the world and be less powerful and obvious, so it does work for gnome haters.

It’s an interesting idea, but if an elf/dwarf or human/dwarf minglings have special names (gnome, halfing), shouldn’t human/elves, human/orcs etc also have terminology other than simply “half-X”?

Also, are these half-castes the rare result of inter-breeding (like a standard half-elf) or are they actually stable offshoots of the parent races?

I particularly like the less clear, more mashed-up version of the gods’ domains. Very nice.

###

What about other, forgotten younger gods? The western elemental pantheon has only four elements, the eastern one typically has five, including wood, metal and void as options.

My personal favourite thing about the eastern elements is that they are in an order; the circle of destruction: fire melts metal, metal chops wood, wood parts the earth, earth dams water, water quenches fire. Or the other way, the circle of generation: fire creates earth (ashes), earth gives birth to metals, metals contain water, water feeds wood, and wood feeds fire.

It’s very cyclic and natural, and might warrant inclusion in the background for Gönd as either an outlawed religion or a (strictly speaking) blasphemous but tolerated interpretation of The Truth(TM). In addition, some druids may instead draw upon this version of the elemental powers rather than the mind-blowing powers of the elder gods.

###

Where does magic actually come from? Is it inexhaustible or does it sap the power of something/someone/somewhere?

###

More questions and considerations to come.

Siltstone, slate, shale, gravel.

The following might be of interest. Tis lifted from the historical belief of bodily “humours” or combinations of four basic elements (Air, Fire, Earth, Water). The two combo’s which are missing are Air & Earth, and Water & Fire. Not sure as to what the former could signify, but the later could be an aspect of dragons, if they are not elementally coloured coded.

Blood: from air, is warm and moist. The term used to describe it is sanguine, and it is considered courageous, hopeful, and amorous.

Yellow bile: from fire, is warm and dry. The term used to describe it is choleric, and it is considered easily angered, and bad tempered.

Black bile: from earth, is cold and dry. The term used to describe it is melancholic, and it is considered despondent, sleepless and irritable.

Phlegm: from water is cold and moist. It is described, rather obviously, as phlegmatic, and is considered calm and unemotional.

I like it and I’m inclined to suggest this as the ‘official’ way of looking at things.

As has already been said, the gods are worshiped as a whole. Perhaps each dawn priests of the religion would pray around the shrines of a temple (or a strong of holy beads, or whatever, if they are travelling) in the ‘positive’ direction to ‘open’ the day. At dusk, they reverse the orientation to ‘close’ the day, thus allowing the world to sleep and regenerate strength for tomorrow.

Perhaps the accepted religion is obsessed with balance as a way to avoid one god reigning supreme and returning us to the ‘bad old days’ of the capricious, unfeeling Elder Gods?

‘Pagans’ could be the formal term for those who worship the Elder Gods and/or dragons. ‘Heretics’ could be a subtly different term for those that focus on a single god or a sub-section of deities, thereby disrupting the sacred balance for personal gain.

There could even be one or two cities that Otraxis trades with, but relations are tense because those cities have ‘patron’ gods – a practice unfathomable to the Oxtrans.

Comments?

General comment, but mainly for Mike and Andrew:

I have real difficulties with heresy or incorrect religious truths in a world where the gods actually walk around and talk to their worshippers. Spells that let you talk to the gods or their representatives can be cast at fairly low levels: augury is a 1st level spell, for example. If a cleric or paladin establishes a new interpretation of the truth that conlficts with what the gods actually want, they lose their spell casting abilities and have to atone.

The only reason heresy and alternate religions persist in our world is because God/gods don’t actually grant spells or speak to people. How long do you think the Catholic Church would have lasted if the Franciscans could cast spells but none of the other orders could, or if Hindus could perform obvious miracles and no one else could?

So, having alternate truths doesn’t work for me in a fantasy game. I am content to ignore it if everyone else prefers it that way, but I think it’s logically inconsistent.

The only good part of Dragonlance was that there were 21 gods and that was it. They ran things, and no one imagined that there were any more or less.

Mike: I don’t mind eastern elements, but it only gives us 5 options, as opposed to the 12 we’ve got. Unless you get eastern paraelements, but I wouldn’t know how to mix Earth and Metal or Wood and Water, for example. It’s not a problem, but it is a consideration.

I haven’t thought about where magic comes from.

Luke: The humours is a good idea, thanks.

Andrew: I did already put the gods into order (so that the seasons line up correctly, and so I could play games with their names and powers), and I like your processional order, opening and closing the day, etc.

The only problem with your balance idea is that Damien said no one remembers the Elder Gods except the dwarves and the dragons.

Ryan:I have real difficulties with heresy or incorrect religious truths in a world where the gods actually walk around and talk to their worshippers … The only good part of Dragonlance was that there were 21 gods and that was it. They ran things, and no one imagined that there were any more or less.

OK point taken. No heretics. The only time we ever have a re-interpretation of the rules is when a real, live god delivers it directly.

So the question is, where do we draw religion-themed conflict from? Are the gods fractious, always working to increase their own personal power? If not, then how do they react if their followers fight amongst themselves? This may amuse Molkai, Chemesh and Enlil (all for different reasons) but many of the other gods seem disposed to benevolence.

I haven’t thought about where magic comes from.

What if magic was actually an impossibly complex but infinitely ordered network of ‘astral’ (please, come up with a better word) threads that underpin and support matter/reality? These threads would have the spectrum elemental characteristics. Those who are properly trained can see the threads.

A wizard casts spells by grasping, tweaking and manipulating the threads (somatic), while chanting at a specific pitch and cadence to make the threads reverberate in useful ways (verbal). Material components are items of special significance that anchor a wizard to the threads even further.

Sorcerers use the threads in a more primal way, sucking elemental energy from them by sheer force of will.

The humble cleric must make requests of the gods, who see fit to reveal the pattern he needs to him, at his specific time of need. This is like an epiphany: the entire webwork around him makes sense just at the instant he casts a spell, then the godlike understanding falls away from him.

Like?

No time for getting to the rest of the posts (I hope tonight), but I needed to jump in here…

And sorry… it’s for a GM vito. “Magic threads” are too close to ley lines, etc.

I’m going to end this one by saying that magic comes directly from the 4 Elder Gods themselves. They have no “divine” manifestations that can be tapped using prayer – so it makes sense that their magical essence can only be tapped (or stolen?) using arcane gesture.

It makes further sense, then, that only the dragons and a select few powerful Elven wizards are even aware they exist. Everyone else has a variety of theories on magic.

Would you decide and be consistent in who knows and who doesn’t? Is it dragons and dwarves (which I prefer) or dragons and elves?

Fair enough. I’m thinking the world building section is getting a disproportionate amount of lovin’ and there could be too many cooks, so I’m going to go back to the City and see if I have any ideas to flesh out the districts etc.

Okay, I’ve just made some updates to the races. I had some notes written simultaneously with Ryan’s excellent contributions… and he’ll be glad to know that I changed my stuff to fit with his wherever possible. I had to include the Elven city because it was in the timeline (and it makes sense that they have some form of central power base), but I made it a living, mobile city.

I’ve also added some notes on the other races of Gönd.

So, I love (LOVE!) the Gods, Ryan. Very nice work there. Let’s lock them in. I don’t want to go into more detail or debate on what the combinations represent, or if we should include alternative cultural elements. It’s not as important as having a great, consistent pantheon – and Ryan has excelled there. Fantastic work.

It is the Elves that know about the Elder Gods and not the Dwarves. I’m not sure where I’ve written otherwise, but I apologise for any confusion. All dragons know about the Elder Gods. Only a select few Elves know – and that information is closely guarded (even from their kin). Those select few are wizards of the highest order, and have been told by word of mouth only. I’ll write up something about it under a Magic section, since it is the raw, primal power of the Elder Gods that fuels the magic in Gönd.

Oh, and I over capitalise words like “Elves” because I’m a Germanic dick. Just anticipating some backlash, there.

When you say, “Elven druids supplied the lumber for human cities”, do you actually mean Druids – semi-heretical worshippers of the Elder Gods? Or just, you know, foresters? If you mean Druids, I’m going to have to reform my conception of this.

I just meant that the Elves gave the humans an alternative to logging. If “Elven Priests” works better, then fine.

I just figured someone with “plant growth” in their spell repertoire could easily stave off a foresting war… and it always struck me as odd that humans kept on having to encroach into Elven forests in any D&D setting that took its spell list seriously.

Are all druids necessarily heretics? If so, it may be hard to have it as a player class. Perhaps only some druids are fully aware of their power’s origins and worship the Elder gods, and the rest just worship “nature”.

If you’d rather remove it, go for it. If you want to rework any of it, go for it, too… perhaps the Elven druids differ from the human ones? Up to you, mate, I don’t want to squash the great work you’ve done so far.

I just thought consistency in the way the classes are presented is important.

It actually works better I think if it’s a secret society where only the high ups really know what’s going on, something like fantasy Masons. (After all, that’s the way Druids used to work in 2e anyway).

So the Druid hierarchy, led by dragons (perhaps dragons in human form, perhaps not – up to you) is secretly working to free the Elder Gods, while the rank and file Druids are just serving “nature” all unawares that every spell that cast brings the Elder Gods closer to freedom…

Or something. Up to you, provided you’re consistent. :)

All agreed. The Hierophants worship the Elder Gods at the past direction of the Dragons – who do not actively lead them, but started the movement. The Dragons have not been involved with the Known World in recent times.